OSAKA—On September 30th, the Osaka District Court delivered a verdict rejecting a lawsuit filed by a Japanese-born university professor who lost her Japanese nationality after acquiring Canadian citizenship, a case that underscores the dual citizenship implications of Japan’s nationality law. The woman argued that Japan’s current nationality law infringes upon constitutional rights, but the court responded that such legislative decisions fall within the discretion of the government and are therefore lawful under the legal framework.

Following the announcement of the decision, the plaintiff held a press conference where she announced she would not pursue an appeal. Nonetheless, she expressed criticism toward the court’s ruling, commenting, “In an era of unprecedented globalization, it’s disappointing that the court is not considering human rights or the realities faced by modern people.”

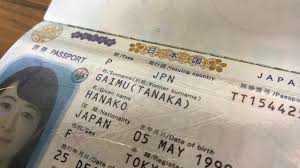

The woman, who is now 60 years old, was born in Tokyo. In 2008, after marrying her Canadian husband, she obtained Canadian citizenship. According to Japan’s Nationality Law, specifically Article 11, an individual who acquires a foreign citizenship automatically loses Japanese nationality — a rule that highlights the dual citizenship implications faced by Japanese nationals abroad. Despite this, she only discovered this loss in 2018 when she attempted to return to Japan at her father’s request, as he was battling cancer. It was during a consultation at the Japanese Consulate that she was informed her Japanese citizenship had been revoked.

Since then, she has acquired a residence visa as a Canadian national and is currently employed at a university in Kyoto. However, she has voiced profound distress over her loss of Japanese identity. Because she cannot renew her Japanese passport, she faces difficulties traveling abroad for work, including visits to Canada, effectively limiting her mobility and ties to her homeland.

In December 2022, the woman filed the lawsuit contesting the automatic revocation of her Japanese citizenship, a case that underscores the dual citizenship implications and the absence of any dual citizenship waiver under Japan’s nationality system. Her legal representatives argued that the Nationality Law contravenes constitutional provisions, particularly Article 22, which guarantees the freedom to emigrate or renounce one’s nationality. They characterized the loss of nationality as “a severe deprivation of personal rights,” comparable in gravity only to the death penalty, and claimed it also infringes on Article 13, which safeguards individual autonomy and dignity.

The Japanese government countered these claims by asserting that the Constitution grants broad legislative authority to define and regulate what constitutes Japanese nationality. It argued there are justifiable reasons for maintaining the current law, such as protecting diplomatic interests—specifically, diplomatic protection offered to Japanese citizens abroad—and avoiding the complications associated with dual citizenship. These include potential conflicts over mandatory military service, taxes, or legal obligations that dual nationality may entail.

The phenomenon of Japanese citizens living permanently overseas—many holding dual nationality—has been steadily increasing. Data from Japan’s Foreign Ministry indicates that as of last October, approximately 580,000 Japanese nationals reside abroad with at least one other citizenship, nearly doubling from around 268,000 three decades earlier in 1995. A significant number of these individuals wish to retain their Japanese citizenship while also enjoying the benefits of their other nationalities.

Legal challenges surrounding Article 11 of the Nationality Law have become more common in recent years, reflecting growing concerns over the dual citizenship implications of Japan’s nationality policy. Several lawsuits have been filed, including cases by entrepreneurs operating in Europe and lawyers practicing abroad who later returned to Japan. Courts, however, have consistently upheld the government’s discretion, citing the importance of maintaining control over nationality rules.

The law itself originated during the Meiji era, when it was enacted in 1899, and has essentially remained unchanged despite subsequent amendments. Under the law, individuals are required to notify authorities if they acquire a foreign nationality, which is interpreted as an automatic loss of Japanese citizenship in such cases. Between 1982 and 2024, more than 36,000 people submitted such notifications, with the number notably increasing in 2022 amid eased COVID-19 travel restrictions.

Attorney Teruo Naka, representing the Osaka plaintiff, remarked that many foreign-born Japanese submit loss notifications reluctantly—often just to obtain visas or re-enter Japan—without fully understanding the law. He suggested that many might be unaware that they are losing their citizenship through these procedures.

Expert research by Professor Atsushi Kondo of Meijo University pointed out that only 38 percent of countries permitted dual nationality in 1960. This figure has risen sharply, reaching 77 percent in recent years, especially among developed nations. Japan remains unique among G7 nations in maintaining a strict single nationality policy, despite international trends towards accommodating dual citizenship.

Maiko Takeuchi, a U.S.-based legal expert and former UN official specializing in economic security, emphasized that international law and precedent increasingly recognize the rights of dual nationals to diplomatic protection. She also noted that Japan’s lack of mandatory military service and the ability to manage tax obligations through treaties lessen concerns about dual nationality.

Takeuchi further argued that forcing individuals to renounce their Japanese citizenship damages their lives and families far more than the government’s concerns about potential issues like military service or tax obligations. Many plaintiffs in similar suits have lost their Japanese nationality for various reasons, such as to gain voting rights, access to public contracts, or eligibility for research projects abroad, thus forfeiting their Japanese citizenship in the process.

She warned that if Japan persists in rejecting dual nationality, it risks a “brain drain.” Talented individuals who have ties abroad may choose to sever their Japanese connections completely, making it more difficult for them to return and contribute to Japan’s innovation and development. Takeuchi called for a major policy overhaul, arguing that Japan’s continued adherence to the “single nationality principle” hampers the country’s ability to remain competitive and innovative in a globalized world.

In conclusion, the Osaka court’s ruling underscores Japan’s ongoing struggle to reconcile its legal traditions with evolving international norms and the realities faced by its expatriates. As the number of Japanese living abroad and holding dual citizenship continues to grow, the debate over the fairness and practicality of Japan’s nationality laws is likely to intensify. Many experts and advocates believe that a reevaluation of these regulations is necessary to ensure human rights, modern flexibility, and the retention of talented individuals who can contribute to Japan’s future prosperity.

Frequently Asked Questions

What are the main dual citizenship implications of Japan’s nationality law?

The law automatically revokes Japanese nationality when a citizen acquires another country’s citizenship. This strict approach has major dual citizenship implications, such as loss of identity, limited mobility, and the inability to enjoy the benefits of both nationalities — a growing concern for Japanese citizens living abroad.

Does Japan allow a dual citizenship waiver?

No. Japan does not currently have a dual citizenship waiver system. Citizens who obtain another nationality automatically forfeit their Japanese citizenship under Article 11 of the Nationality Law.

How many Japanese citizens are affected by dual citizenship rules?

According to Japan’s Foreign Ministry, about 580,000 Japanese nationals live abroad with at least one other citizenship, nearly double the number from 1995. Many want to retain Japanese citizenship while benefiting from their other nationalities — an issue central to ongoing dual citizenship implications.